Ostrów Mazowiecka

|

|

The house in which Public School No. 3 was located |

Government Public School Number Three

By Izrael Sztejnberg

Translated by Judie Ostroff Goldstein

In the government public school for Jewish children, Jewish students from Ostrowa studied and were educated. The total number of students reached a high of eight to nine hundred and the number of Jewish teachers reached twelve. This was the largest Jewish educational institution in Ostrowa. It was a normal government public school consisting of seven grades.

The Polish public schools (previously established) were also open to Jewish children and the Jewish school was open to Poles. No Jewish child was ever sent to the Polish public school – and Polish parents would never enroll their child in government school number 3. It was an agreement, not in writing, between the Jews and the Poles. The Poles did not want their children to be friends with Jewish students, and the Jews did not want their children to become assimilated or have to go to school on the Sabbath and Holidays.

The students of the public school (for Jewish children) were recruited from a) the poor working-classes such as: porters, unskilled labourers, artisans, street peddlers; and b) Hasidic circles. The Hasidim sent their boys to heder or “Yesodi HaTorah” and the girls – in the morning to the public school and in the afternoon to “Bes Jakob”. The number of girls in the school was quite large (over eighty percent) and their were classes of only girls.

|

|

A class in the government public school |

|

|

A class in the public school soon after the First World War – with teachers |

|

|

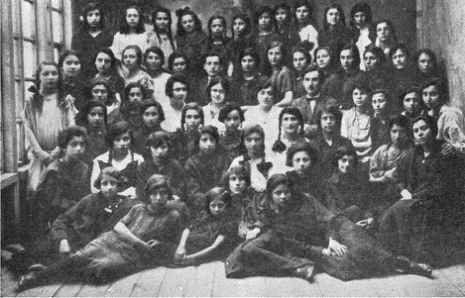

Older students in the public school |

|

|

A class in 1924 |

The principal differences between the above mentioned school and other free Polish schools was:

- The rest day was Saturday. Sunday was a school day. The school was closed for all Jewish holidays.

- The pupils studied Jewish religion (two hours a week in every class).

I must mention the great effort made by Arija Margolis to find a teacher for Jewish religious classes. His search was successful and in 1925 the Jewish religious teacher was Abraham Borlas, a graduate of Poznański's Seminary in Warszawa and an educator in the famous children's home under the direction of the writer and pedagogue, Janusz Korczak.

Abraham Borylas took teaching very seriously and in the two hours per week allotted him (per class) he managed to instill a little Judaism in his students. He even tried teaching Hebrew. With his lectures and enthusiastic stories, his class became one of the most popular. For the subject Jewish Religion, the students were provided with wonderful books in Polish. They learned stories from the Bible and studied Jewish history. They learned about Jewish leaders, holidays and a small overview of Jewish history in Poland.

All the subjects in the public school were taught in Polish, even though the school had a Jewish atmosphere. At break, amongst themselves, the students spoke only Yiddish. The teachers tolerated Yiddish being spoken, even though they were more interested in the students mastering oral and written Polish. The children also spoke Yiddish at home, still they did not fall behind the Polish students.

The government visitors and inspectors quickly realized that the Jewish students were eager to learn and had a desire to excel in their studies. The teachers never had any complaints about students' conduct in the classrooms. The students were well behaved and the majority paid attention to the lectures.

A lot of the children were poor and did not get enough to eat at home, but still excelled in school and took an active part in the children's communal work.

I would like to mention the excellent work that the children did in the school cooperative, where the students shopped for school supplies at inexpensive prices. They ran their school store with honesty and generosity. They worked hard in the school library. Later, with help from the teachers, they organized a bookbindery to repair and bind books for the school library.

The mandolin orchestra was well run by the students under the direction of the devoted teacher Blumowicz.

The principal activity was the Dramatic Circle, under the direction of the devoted teacher Henje Szternberg. The Circle became famous for its presentations.

The students were to be admired for the help they gave each other with their schoolwork.

The weaker students in the lower grades were assigned a good student from one of the higher grades as a tutor. The atmosphere in the school, between students, was more like a club.

The school building – a wooden one – was far from beautiful, the same for the equipment, but thanks to the teachers' skills and knowledge and their love and devotion to the institution, a good educational program was put in place and the school had a good reputation in the district.

|

|

A class in 1925 |

|

|

A class in 1927 |

|

|

A class in 1927 |

|

|

Grade V in 1932 |

The teachers were locals and so they could give more time to their work. In the last years before the outbreak of the Second World War, the teachers organized evening classes in the school to help the artisans pass the exam for their government accreditation as tradesmen. This was an important achievement. The majority of the Jewish artisans had learned their trades from their fathers or grandfathers, but now they went to school to learn. In Poland at that time there was a trend to keep Jewish artisans from getting work. The qualification commission was strict in its interpretation of the rules when it came to Jewish artisans and very often refused to give a work permit or trade diploma on the pretext that the last owner did not have enough knowledge. Therefore the courses were very important. I was a struggle against invalidating Jewish artisans and taking from them the little they earned.

There was an active parents committee at the school and they helped to improve the educational work in the school and to keep in touch with the mothers and fathers of the students.

As already mentioned, a large number of children came from poor, large families living in one room. The parents' committee and the teachers organized relief for them. The poor children were provided with books, shoes and clothing.

The children received breakfast in school (cocoa and sugar was given by the municipal government). Mosze Raf, the teacher and councilman, worked very hard to get the breakfast program for the school.

The relationship between the parents' committee and the teachers was one of mutual respect.

Once during a market day the Endekes youngsters in town went wild and turned over the tables of the Jewish merchants in the marketplace. It happened when the Dramatic Circle was putting on a play at school for the visit of the inspector and several guests. The play was based on Polish history and had a patriotic theme. The child-actors made remarks that the tables of the Jewish merchants should have been put back in place and were asking if they should go on with this Polish play about Polish rich men of old. I understood what they were trying to say and calmed them down. Due to the interruption of the already started play, it was difficult to explain about the government factors. We must strongly denounce and fight against anti-Semitism that targets Jews and also shames Poland and the Polish people. On the other side, we are loyal citizens of the country. Both the parents and the children had full confidence in the teachers. They knew that the school was not just an educational institution that enriched the children with knowledge, but also an institution that taught the students to be good, free, useful people and faithful Jews.

Often, particularly during inspections, we would experience anti-Semitism and rudeness. The principal inspector would greet all the Polish teachers and ignore the Jews. The Jewish teachers thought that the true purpose of these conferences was to find fault, instead of providing guidance.

The principal inspector had called upon the teacher Zofia Hut and when she would not agree to give him her observations, he became very angry and wrote his opinion in her personnel file. She was devastated and became ill. The writer went to the school inspector to intervene. Once again the principal inspector visited Zofia Hut's class. She was still sick and I represented her. The inspector listened to the children and everything was okay. The principal inspector corrected his opinion in her file about her work. But several moths later she died of a heart attack.

The Jewish teachers in the public school were all qualified, but some were more gifted than others. Some had more work experience, others less. But all of them without exception strove to improve their knowledge. They all took part in the monthly pedagogical conferences, together with the Polish teachers.

There were two sample lessons and lectures given. Our school had in its turn arranged these conferences. The ambition of the Jewish teachers was to present high quality sample lessons and lectures.

The school had a good reputation and respect for the teachers grew. The program from an educational standpoint was good. But from the national standpoint, in my opinion, Jewish education was not thorough enough, yet (compared to other schools of this type in other towns) was free of assimilation tendencies. To the teachers' credit, there was no assimilation among them. Even the one (Frankfurtski) who did not understand Yiddish. All of the teachers were members of various Zionist and community organizations and a large number of them took part in Jewish community and cultural life. One of them actively worked in the Zionist organizations. This also influenced the students and they became involved in “Bes Jakob”, HaShomer HaTzair and the scout organization “Fraihait” [“Freedom”].

I would also like to write a few lines about the founding of the school:

After the years of German occupation during the First World War, there were two Jewish public schools. One school was for boys under the direction of Mosze Holcman and the second for girls under the direction of Mosze Raf. Both teachers were active in the community.

After Polish independence in 1918, both schools were combined into one co-educational school that was state run and became known as Government Public School Number 3 in Ostrów Mazowiecka. The public government school for Jewish children existed for twenty-one years (until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939).

The following educators and teachers worked at the school during its existence. (The names appear in alphabetical order):

Borlas, Abraham |

Epsztejn, Fejgl |

Bankier, Sala |

Fabian, Zosia |

Blumowicz, Icchok |

Frankfurtski, Edek |

Glinka, Leah |

Koplewicz |

Holcman, Mosze |

Raf, Mosze |

Hut, Zosia |

Raf, Pesia |

Zlotkes, Bela |

Raf, Clara |

Ciechanowicz, Ester |

Rekant, Bracha |

Lawka, Hawa (Ewa) |

Rozenberg |

Langholc, Hilek |

Sztejnberg, Israel |

Landau, Ida |

Szternberg, Henja |

The teachers working at the school at the outbreak of the Second World War were as follows: Bankier, Blumowicz, Lowska, Frankfurtski, Raf Mosze, Raf Pesia, Szternberg and Sztejnberg. Six of the eight above mentioned teachers, were murdered by the Nazis and two (Blumowicz and Sztejnberg) were miraculously saved and live in Israel.

The Nazis murdered the majority of students and teachers from the public school for Jewish children.

The names of the tortured slaughtered and cremated Jewish children and their teachers will always be remembered. Despite our enemies, we will continue to spin the golden threads of Jewish knowledge, of Jewish national culture in our Jewish home, Israel, where we will raise a new, healthy, Jewish generation that will no longer tolerate the lawless spilling of Jewish blood.

|

|

Sitting from right: Zlotkes, Frankfurtski, Glinka and Ewa Lawska. |